Reflections about Snake Lake, Poland, Hate – and Your Senior Thesis

I wrote this blog post originally for the CSoc Blog – describing how Comparative Sociology faculty and senior thesis students spent a Saturday in early September from 10 am to 4 pm, working together to demystify the research process involved in producing a senior thesis.

Just before leaving my house on a Saturday morning for the senior thesis retreat at the Tacoma Nature Center at Snake Lake on September 8, I briefly checked my Facebook news feed and came across this disturbing reproduction of a tweet that had been earlier posted to Twitter:

“Someone needs to assassinate Obama…like ASAP #DieYouPieceOfShit”

I barely had time to re-post the link and the quote with my own brief comment about the poster (“Right-wing hatred from a 16 year old girl”), before I had to leave for day’s event. But in the moments before the first CSoc faculty-led panel discussion started, looking out through the open half-wall of the upstairs meeting room where our retreat was being held,

seeing the peace and greenery of the Snake Lake environs outside, and recalling so many nature-exploring trips to this place 20+ years ago with my then young sons, I was brought back in thought to the general theme of the book I will begin writing during my sabbatical this coming spring. The larger human issues I want to address in this book also concern hate, but certainly not just hate alone. Months ago I had typed three short bullet points into my Mac Notes program, trying to pin down for myself what my proposed book project was really about, deliberately avoiding all academic language and references. I will copy and paste those points below, revealing in this way the messy, repetitive, perhaps even contradictory and logic-challenging way that my mind begins a major writing project.

- This book will be about embracing, with love and enthusiasm, one’s personal ethnic heritage, even though such a heritage also demands a confrontation with ugliness and horror and raises questions about collective identity if not collective guilt. My awareness of these contradictory impulses came upon me slowly, over the course of more than a decade, as a result of my three trips to Poland (the last two with each of my sons, one at a time), including my very deliberate decision to go with them and show them the death camps at Auschwitz as well as much more pride-affirming Polish historical sites.

- This book was inspired by my contradictory responses – shame/horror as well as love/pride – that were set off when I happened to watch a particular YouTube video just after returning from a family heritage trip to Poland the summer before last.

- This book will grapple with the contradictory impulses faced by people whose “own people” (family, ancestors, ethnic group, or other significant community to which they feel a sense of belonging) includes both perpetrators of evil as well as bringers of hope. For me personally, the moment that triggered my sharp awareness of this duality of heritage crystalized after two online viewing experiences that occurred shortly after I returned home from a trip to Poland in August 2011. First, I saw a picture and read an online account from an English-language Polish news source documenting the spray-painting of a swastika on a memorial put up to commemorate a massacre of Jewish townspeople by their Polish neighbors in 1941 – an event which figures prominently in the class I teach on genocide. My immediate emotional response? No, not again…. Then, shortly afterwards, I happened to find and watch a YouTube video of the Polish folk group, Trebunie-Tutki, performing and playfully interacting with the Jamaican reggae group Twinkle Brothers, all filmed in the gorgeous Tatra mountain resort town of Zakopane. My emotional response this time? A strong, heartfelt, grateful Yes!

Hard to follow, isn’t it? What do these three bullet points have to do with the tweet I cited above about someone wanting Obama assassinated? And how does any of this relate to the senior thesis retreat?

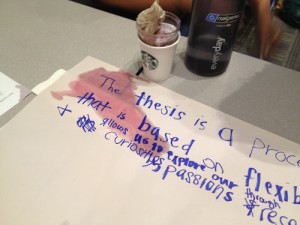

Let me tell you a little more about all of these blurry-edged intersections of emotion and stimuli, facts, and interpretations, hoping in this way to continue what I believe we started to do together at Snake Lake: demystifying the process of identifying and developing a research topic, turning that into a research question, and proceeding to write about one’s findings in a way that resonates with a particular discipline – in this case, anthropology or sociology.

My upcoming sabbatical will be devoted to preparatory research for a book I have set out to begin writing which I have tentatively titled Symphony of Sorrowful/Joyful Songs: Facing, Loving, and Teaching Poland. The phrase “symphony of sorrowful songs” is actually borrowed from the title of a deeply moving piece of modern classical music composed by Henryk Górecki – his Third Symphony, in which each of the three symphonic movements incorporates a soprano singing anguished words about a mother’s loss of her son because of war or death, and a daughter’s separation from her mother because of her political imprisonment and impending execution by the Gestapo – themes that are all too well understood by Polish people.

Music is a huge part of who I am, both as an individual and as a member of my particular family, so it is no surprise that I want to write about it here, but there is so much more I want to incorporate in this project as well. In addition to the Górecki symphony (parts of which have been performed at the execution wall at Auschwitz) I am also interested in other twenty-first century Polish music as it connects with those murky themes I began trying to articulate above. Rootz music – a fusion of Polish folk music, music of the Balkans, world beat, techno, dub, klezmer and other eclectic musical genres and influences – most definitely will find its way into my investigations too.

Perhaps even more than the music itself, I am interested in the young Polish musicians who are creating, experimenting with and performing this music. For reasons directly related to the Holocaust and the subsequent anti-Jewish social climate that occurred in Poland even after World War II, most of these musicians are not Jewish or “ethnic folk” themselves.

And yet these young people are insistently rediscovering and reinterpreting earlier Polish and Jewish musical traditions – klezmer and Polish highlands folk music in particular – in ways that are startlingly new and creative.

Furthermore, all this is taking place in a larger social setting that is marked not only by pro-capitalist, pro-consumerist fervor, but also, in select circles, a genuinely critical attitude toward the present adulation, in some quarters of Polish society, of EU market and high-end consumer priorities and desires, coupled with a deep interest in historically long-term and surprisingly complex Polish attitudes toward ethnic minorities. And this history sadly also includes the specter that is always threatening to rear its ugly head again: right-wing, nationalist “ethnic purity” movements.

Perhaps this messy concatenation of themes – the worst human manifestations of evil juxtaposed against some of the most vibrant affirmations of the human spirit through music – explains why all these ideas came together for me in such a personally meaningful way when I saw the hate-tweet just minutes before setting off for the senior thesis retreat.

The relationship between hatred/fear and the desire to annihilate “the other” who inspires this hatred can, I believe, be understood in Durkheimian terms as not only fear of the outsider, but at an even deeper level, as fear of contamination. The dark-skinned man with the Moslem first and middle names, the supposed Kenyan rather than American birth, the sinister Marxist plotting oppressive domination – these are actually comparatively mild images of “otherness” compared to the much more diabolical images of Obama that appear on the hate websites currently monitored by groups such as the Southern Poverty Law Center. Similarly, in my class on genocide I must every year explain to students that yes, people in twentieth-century Europe really did believe that Jews kidnap Christian children to drain their blood to use in making matzo for secret Passover ceremonies. How terrifying such images must be to xenophobic fundamentalists who fear, at the deepest level of their being, being swallowed up or fatally polluted by what they regard as such demonic otherness!

I cannot possibly expect to fully answer the Why and How questions about this kind of hatred – or about creative attempts by artists to transcend it – in one book or even a lifetime of writings. But it is so important for me – first of all as a mother of now-grown sons, and certainly as a teacher of thousands of students over the course of my career – to try to do my part handing down to the young generation some tools to unmask the ignorance that can incubate such poison.

Snake Lake was a perfect place for me to weave together my personal biography and my professional training and interests in connection with a research and writing project of my own. I heard my CSoc colleagues talk and I got very excited thinking about all the different ways that such a project (my own!) can be approached and articulated. I looked out the half-open wall overlooking all that greenery and I got very nostalgic about all the evening walks I once took there with my then-little boys, showing them where the giant anthill was, but cautioning them solemnly “not to tell anyone” because “mean people might kick it down”. Even at that early age, I guess, parents need to prepare their children for the existence of evil in this world.